When Newt Gingrich appeared on "Meet the Press" a week ago, the conservative heartthrob (for those with strong hearts) strongly hinted at a late-starting presidential bid: "Well, I'm thinking about thinking about running. But I won't do anything at all about the possibility of running until after Sept. 29," a date that would coincide with the 13th anniversary celebrations hailing the "Contract With America."

Promoting his latest book last Monday in New Hampshire -- a state better known for its presidential primary than as a way station on author tours -- Gingrich rejiggered his decision-2008 timetable and also began invoking the royal "we." Asked about his presidential plans, the former House speaker said, "If we do anything, we would probably do it on Nov. 6," precisely a year before the 2008 election.

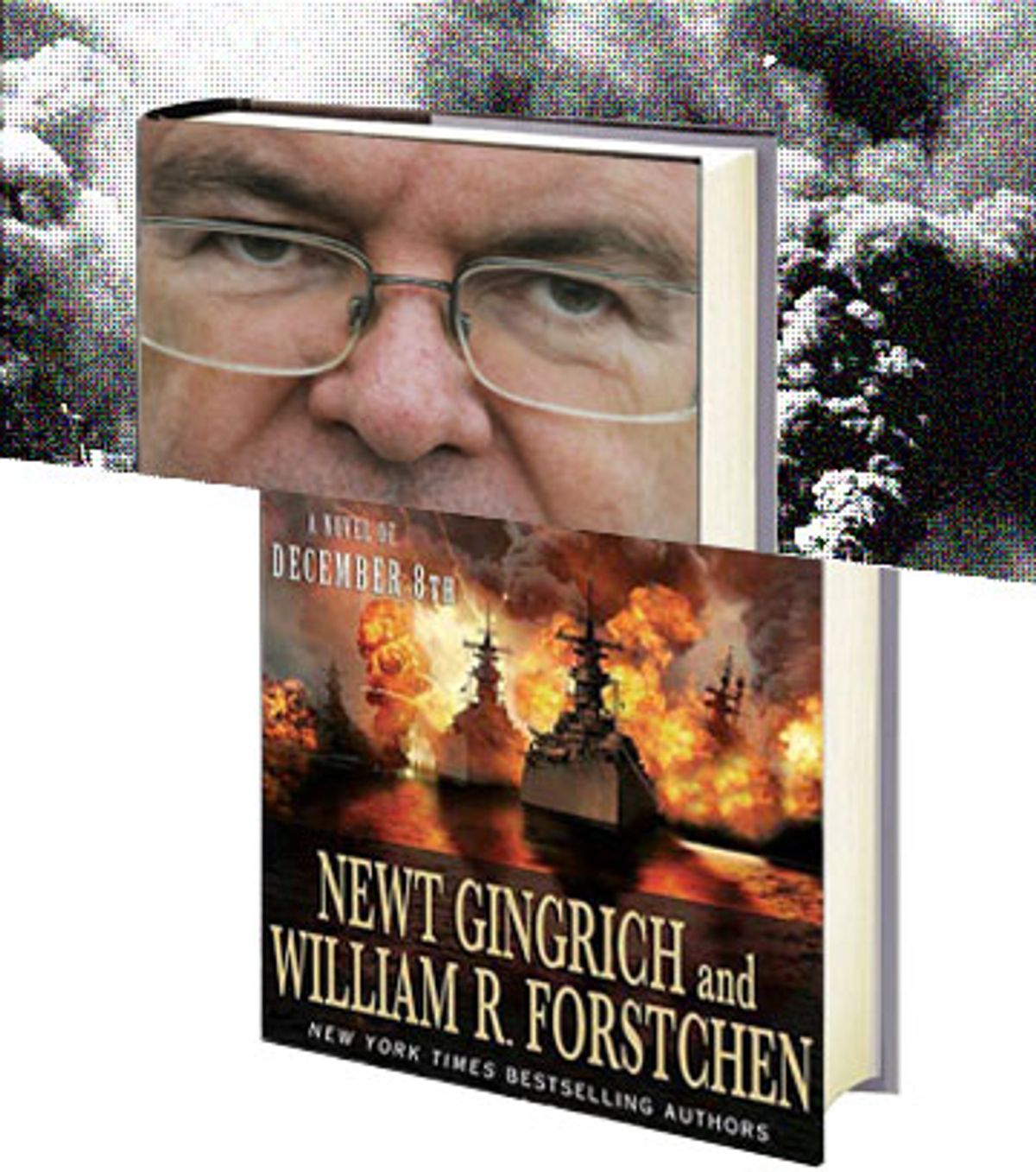

Despite the verbal flimflam, Gingrich, who relinquished the speaker's gavel under an ethical cloud after the 1998 elections, unequivocally is running for president. The definitive evidence is embedded in the text of his latest novel, "Pearl Harbor," a what-if alternative history cobbled together with his longtime novelistic collaborator, William R. Forstchen. (The writing-by-committee style is suggested by the additional presence on the title page of Albert S. Hanser, listed as a "contributing editor.")

But no matter how many hands were at the computer keyboard, or moving model battleships around a naval map of the Pacific, Gingrich is the one whose reputation is on the line -- and we are not talking about the National Book Awards. The 63-year-old former history professor, who is in the midst of a Nixonian comeback attempt, cannot afford to have his plus-size ambitions complicated by embarrassing passages in a novel that presumably he co-authored as something of a lark.

So Gingrich played it safe. Every sentence in "Pearl Harbor" would pass moral muster with the hymn-singing graduates of Liberty University, where Gingrich was the sad-eyed commencement speaker last weekend mourning the death of its founder, Jerry Falwell: "As friends and family gather this week to bid Jerry farewell, let us trust in the Lord that, some glorious day, we shall see him once more."

As Gingrich juggles the contradictory demands of novelist, putative presidential candidate and Falwell friend, what is notable about "Pearl Harbor" is what is missing. In the novel, there is not a single sex scene nor -- to remove all heterosexual temptation -- even a single female character. OK, at the very end of the novel, with Battleship Row devastated, a wounded naval officer returns home to his wife: "He was afraid to put his injured arm around her, she was wearing her favorite Sunday dress, ivory colored, close fitting." Those two words -- "close fitting" -- are about as hot and heavy as it gets. The Cub Scout Handbook is a racier document.

Before he was seized by the presidential bug, Gingrich wasn't nearly as circumspect. His initial fictional collaboration with Forstchen (a novel titled "1945," which envisions a triumphant Hitler dominating postwar Europe) was studded with inadvertently comic sentences like, "Suddenly the pouting sex kitten gave way to Diana the Huntress." But that unforgettable line (think Jacqueline Susann meets Bulwer-Lytton) was published back in 1995 when Gingrich was the personification of hubris, seemingly convinced that the Republican takeover of the House was a historic transformation on par with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

While Gingrich's puffed-up persona and tangled marital history are easy to mock, the former speaker has long been the most intellectually intriguing figure on the Republican right. These days, most conservative politicians (Tom DeLay, Mitt Romney, Mitch McConnell) lack ideas; Gingrich suffers from having too many of them. It is important to realize that many Republicans hail Gingrich as a visionary, much as Al Gore is lionized by Democrats. (To be precise, I am not equating Gore and Gingrich as prophets and political leaders, but pointing out that they play analogous roles as "thinkers" within their respective political parties.)

A case in point is Gingrich's fascination with reimagining history, grappling with the hard-to-accept realization that major events in the past were not foreordained. These thin strands of fate were depicted 250 years ago by Benjamin Franklin when he wrote, "For want of a nail the shoe was lost; for want of a shoe the horse was lost; for want of a horse the rider was lost." In Gingrich's hands, this maxim from "Poor Richard's Almanac" would extend to battles, wars and the fate of civilizations. While Gingrich is a foreign-policy hawk and an unswerving supporter of the Iraq war, his enthusiasm for historical speculation is at odds with the guiding philosophy of the Bush administration, which appears to be built on the bedrock of God-given certainty.

As an event, Pearl Harbor has obvious resonance for our time, evoking both the emotional horror of the Sept. 11 attacks and the last gasp of Greatest Generation nostalgia. But the patriotic sentiment surrounding the "date that will live in infamy" can easily be exploited by conservatives of different stripes.

The Dick Cheneys of this world will perpetually point to Pearl Harbor as proof that America's enemies are lurking just over the horizon -- and the only prudent response is preventive war. For America First isolationists like Pat Buchanan, the Japanese assault on the American fleet can be portrayed as a manifestation of Democrat Franklin Roosevelt's perfidy. The reigning right-wing conspiracy theory from the 1940s is that FDR deliberately ignored the warning signs of a Japanese move on Pearl Harbor in order to create the cataclysmic event that would needlessly propel America into World War II.

But Gingrich and Forstchen (who also co-authored three Civil War novels) do not manifest this kind of paranoia, xenophobia or the heavy-handed settling of historical scores. Rather, they are enthralled with the Great Man theory of history. A typical episode begins: "'Franklin, I will miss you when we part today,' Churchill smiled warmly at his friend and ally. 'Our new Atlantic Charter sets the moral stage for what we must do.'" This painful passage underscores the authors' artistic limitations when it comes to replicating realistic dialogue.

As near as I can tell, Gingrich and Forstchen are on far firmer footing when it comes to the details of military history. Had I not consulted a few reference works before reading "Pearl Harbor," I might have innocently assumed that this so-called novel was merely a lightly fictionalized version of the familiar story, distinguished primarily by its nuanced and sympathetic appreciation of the Japanese navy. Only military history buffs will recognize that the pivotal scene in "Pearl Harbor" is the completely fictionalized decision by Adm. Isoruku Yamamoto, the commander of the entire fleet, to personally direct the attack. By placing the daring Yamamoto on the scene -- rather than his cautious subordinate Vice Adm. Chuichi Nagumo, who was in charge in real life -- Gingrich and Forstchen give history a strong shove.

The what-if aspect of the novel is built around the premise that the Dec. 7 attack would have been far more militarily devastating if the Japanese had launched a third strike and destroyed Pearl Harbor's naval-repair facilities and its oil-storage capacity. In reality, such a continuation of the onslaught was proposed by Japanese pilots who returned to their aircraft carriers, only to be rejected as too risky by Nagumo, their commander.

The final 65 pages of the novel -- which depict the attack on Pearl Harbor, including the mythical third wave -- read like the script for a video game or the instructions for a life-size historical reenactment. Americans witnessing the air raids from the ground stalwartly refrain from uttering a single four-letter word. About the closest anyone comes to losing self-control is the veteran U.S. naval officer who looks up at a Japanese pilot and thinks, "Whoever was in that plane, he hated the bastard and yet he could not help feel some admiration as well ... the son of a bitch." Thanks to Gingrich and Company, we now know that 60 years of war novels and movies (from "The Naked and the Dead" to "Apocalypse Now") have been completely wrong -- soldiers under fire never resort to language that might offend Jerry's Falwell's academic heirs at Liberty University.

"Pearl Harbor" is billed as the first installment of a Pacific War Series. The authors do not offer a sense of their larger artistic vision in the text; the novel ends with Adm. Bull Halsey melodramatically intoning, "By the time we are done with them, Japanese will only be spoken in hell."

But in his "Meet the Press" interview, Gingrich hinted at the contemporary lessons that will be embedded in his ongoing re-creation of the war against Japan. Stressing the need to prevail in Iraq, he said, "I just did a novel on Pearl Harbor and the Second World War. The Second World War was hard. Guadalcanal was hard. If we'd had today's Congress during Guadalcanal, the number of people who had said, 'Beating the Japanese is too hard, let's find a negotiated peace,' would have been amazing."

While Gingrich may not have time until he and Forstchen win WWII all over again -- and an interlude in the White House would only delay matters further -- it is easy to imagine what should be his next big literary project. In the annals of alternative history, nothing could match the inspiring what-if story of how America won the Iraq war.

Shares