No book contributed to America's popular image of political greatness more than John F. Kennedy's "Profiles in Courage." Kennedy, as his choice of title suggests, lauded the classical virtue of courage, something he would have in common with William Bennett, whose "Book of Virtues" celebrated Homeric bravery more than it did Christian virtues such as compassion. Emblematic of Kennedy's pantheon of political heroes was Missouri Sen. Thomas Hart Benton who, under fire from his Southern colleagues for his opposition to slavery, which also made him increasingly unpopular at home, refused to modify his strong support for the Union. "I despise the bubble popularity that is won without merit and lost without crime," he wrote after the legislature of his state elected someone else in his place. "I sometimes had to act against the preconceived opinions and first impressions of my constituents, and I have never been disappointed."

The Kennedy-inspired appreciation for courage lives on; later this month, Hyperion books will publish "Profiles in Courage for Our Time," a collection of essays edited by Caroline Kennedy. Although the original book included only senators, this time one president is included: Gerald R. Ford, for his unpopular pardon of Richard Nixon. Otherwise, whether the praise goes to former New Jersey Gov. James Florio for his support of gun control, or Sens. John McCain and Russ Feingold for their diligence on behalf of campaign finance, the lesson Caroline Kennedy's father taught is reinforced: Great leaders are those who buck the tides.

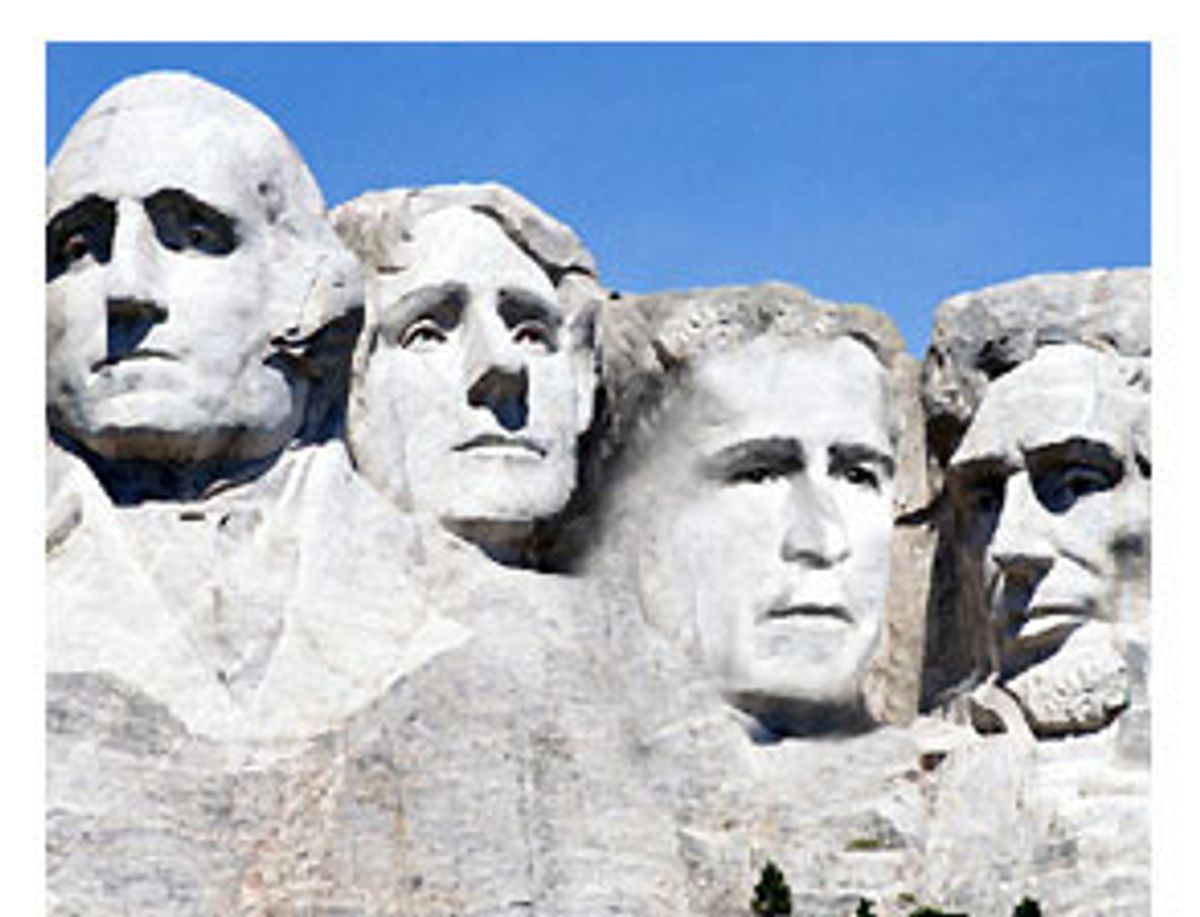

It is not too early in the Bush presidency to speculate about how he will be judged by the standards we have traditionally used to evaluate our political leadership. Both popular mythology and academic analysis have had a lot to say about who our great leaders have been -- and why they have been great. And by the "Profiles" standard, one ought to immediately begin to include George W. Bush among the elect. Politics is a notoriously unpredictable business, but if Bush serves two full terms, the future is likely to include not only a significant shift to the right with consequences that will be felt for years, but a return to the days, seemingly gone forever during the Vietnam years, when an "imperial presidency" dominates the political landscape, rendering all other institutions of government to secondary roles.

And Bush, like a character out of Thoreau, has done all this by walking to the beat of his own drummer. Consider his proposed tax cuts. There has never existed strong public backing for the cuts President Bush has made the centerpiece of his domestic policy. Expert opinion is close to unanimous that current conditions require steps to bring deficits under control rather than to expand them for the foreseeable future. Yet nothing seems capable of deterring him from pursuit of a policy he is convinced is the right thing to do. Whether you admire or detest him -- everyone in America seems to be in one camp or another -- you have to conclude that vacillation is not in his political genes. Like every other president, Bush follows the polls, but while support for tax cuts can go up and down, his position never changes. Even his harshest critics ought to find something admirable in a man so intent on sticking to his convictions.

Bush's consistency on domestic policy pales in comparison to the determination he demonstrated over Iraq. Unlike Bill Clinton, who never could seem to make up his mind whether U.S. power should be used to stop genocide in Rwanda or Bosnia, Bush had no hesitation in confronting Saddam Hussein. Polls showed that Americans clearly wanted the president to win the support of the U.N., as well as that of our allies, before going to war in Iraq; he went ahead without the former and with only a few of the latter and, lo and behold, public opinion followed him. World opinion -- or so we once believed -- matters in foreign policy, yet the president was perfectly willing to make enemies in Europe to defeat his enemy in Baghdad. And, at least until now, he has been rewarded for showing the courage of his convictions. By standing firm, he has made everyone else look weak. Gamblers tend to win big -- when they win. Bush took genuine risks and has not been shy about claiming the pot.

And yet Kennedy's choice of Thomas Hart Benton suggests what, besides courage, goes into the definition of great leadership: Benton was not only firm, he also happened to have been right. There were other politicians whose convictions in favor of slavery were as strong as Benton's feelings toward the Union, yet we do not include Sen. Henry Foote of Mississippi -- who at one point in a heated debate with Benton on the Senate floor pulled a pistol and threatened to use it -- among our great leaders. Kennedy's book deliberately included politicians to celebrate whose decisions turned out to be good for their country. (This does not mean that all of them were liberals; "Profiles in Courage" includes a portrait of Mr. Republican, Sen. Robert A. Taft of Ohio, who was celebrated for his fidelity to strict constitutionalism, even as his position led him to be quite critical of the Nuremberg trials.) Published one year after the U. S. Senate censured Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, "Profiles in Courage" wanted to leave the impression that the best leaders were builders of a strong society, not those whose shortsightedness threatened to tear it down. Can anyone, at this moment, make that claim about the Bush administration?

When they discuss great leadership, academics often pick up where "Profiles in Courage" left off. For fields riven by political and methodological dispute, political science and history hold a strikingly consensual view of presidential greatness: Washington, Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt are nearly always in, while John Adams, Ulysses S. Grant and a host of others more likely to appear in trivia contests than textbooks make up the worst. (Not even David McCullough's hero-worshipping biography of Adams persuaded this reader of his presidential greatness.)

Not only is there surprising agreement among academics on who was great, there is something of a consensus on what made them great. Washington's decision to step down created a two-term tradition that has helped the country avoid monarchical temptations. Jefferson's purchase of Louisiana paved the way for the nation to become a continent. Jackson was responsible for modern democracy as we understand it. Lincoln put defense of the Union ahead of everything else, even civil liberty. Roosevelt's New Deal as well as his World War II leadership saved the country from depression and fascism. We live in revisionist times when yesterday's truths are continuously reexamined; Andrew Jackson, for example, is unfashionable these days for his cruelty toward Native Americans, indeed his cruelty toward everyone. Yet no one has tried to make the case that Lincoln should have been more willing to compromise with Jefferson Davis, or Roosevelt more believing of the professed intentions of Adolf Hitler. Their judgment has stood the test of time.

Making the right decisions, however, is not enough. As political scientists Marc Landy and Sidney M. Milkis argue in their fascinating book "Presidential Greatness," our great leaders have been tutors; as Felix Frankfurter said of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, they take "the country to school." One way they do so is through their eloquence. Kennedy himself did not live long enough to influence American policy, but his words were sufficient to include him among the presidents who will always be remembered. Ronald Reagan shared little with Kennedy, but he too spoke words that are unlikely ever to be forgotten.

Eloquence may well be the most misunderstood characteristic of leadership. It is not, as many believe, a talent that can be mastered by good coaching, nor is it something that comes naturally to some people while resisting the best efforts of others. Eloquent presidents, rather, are those who perceive a need the public does not even know it has and find the right words to address it. Eloquence is the opposite of both manipulation and demagoguery. The manipulative leader perceives correctly what people really need and then tries to persuade them that they need something else. And the demagogue takes the needs people are persuaded they have and reinforces them, even when people's perceptions of their own needs are incorrect; demagoguery flatters, while eloquence elevates. Presidents who manifest eloquence intuitively understand what people would choose when they are guided by what our most eloquent (and without doubt our greatest) president, Abraham Lincoln, called the "better angels of our nature."

Leaders educate not only by the words they speak; they also understand how much time it takes for their lessons to sink in. Franklin Roosevelt knew that Hitler would have to be defeated militarily with America's help. He also knew how powerful isolationist sentiment could be in the United States. Like any great teacher, Roosevelt handed out his lessons in doses, watching to see how prepared Americans were to accept the new responsibilities being placed upon them before placing even more.

Characteristic of his approach was the way he handled the Lend Lease Act of 1941, a program of military support to Great Britain. The administration went to great lengths to show that Britain was unable to pay for its own defense (to the consternation of Churchill) and that we would help them by lending rather than granting them money, all the while realizing, without ever saying so, that once we were in this far, it was only a matter of time before the American public accepted the need to enter the war on the British side. Roosevelt realized that one of his predecessors who came close to greatness, Woodrow Wilson, eventually failed the test because he lacked the patience to explain why his policies, even when they were right, should be accepted by ordinary people.

So if courage is the defining quality of leadership as Kennedy understood it, wisdom is the quality most often emphasized by political scientists and historians. When Lyndon Johnson, not one of our greatest presidents, found himself in that quandary called Vietnam, he turned for advice to a group of foreign policy advisors dubbed "the wise men." That might not have proven an apt description. But his instincts, at least, were right; at crucial turning points in our nation's history, presidents ought to try to do what is neither popular nor principled but what is wise.

Is George W. Bush, for all his steadfastness, either wise himself or capable of relying upon others who are? There is considerable reason to doubt it. Of course he made the right call on Iraq. Or did he? It does not take wisdom to win military battles; ammunition usually does that. But it does take wisdom to achieve Bush's larger goal of creating post-Cold War global stability. Is it wise for America to be taking on the drawing of a new global map without the support of the United Nations and against the wishes of most people in the world? Would a wise president, moreover, begin such a huge undertaking without any effort to prepare the American people for the costs his ambitions will impose? Does generous magnanimity better serve the president's goals at this time than churlish resentment? The very determination that led Bush to neglect his critics and to accomplish so quickly his military victory in Iraq is the enemy of the wisdom he will need to repair the political damage that will follow if no weapons of mass destruction are found there or if religious fundamentalism replaces democratic dreams once American forces leave.

With respect to the military victory in Iraq, the president got something right. But when it comes to his domestic agenda, his programs are as unwise as any can be. Missing from the way in which Bush argues on behalf of his tax cut is any sense that the prospects of future generations will be severely crippled by the fantastic sums the government will have to expend in interest payments to cover the deficits his policy seems designed to produce. No tale of fiscal woe from governors, even those of his own party, moves him. No knowledge of what has happened in history when governments have acted with fiscal irresponsibility matters to him. It is as if the actual country, its families and their lives, are secondary to his inward determination never to back down on a promise that only the extreme right wing ever recalls him making. His policies are those of a man more concerned with the strength of his political base than the strength of his country.

Under this administration, in other words, the president does not tutor the public; on the contrary, from economists to newspaper editorialists to even a couple of Republican senators, the entire country has united behind an effort to instruct the president. This is not the first time in American history that one element of the political system has patiently tried to educate the other about the rules of public finance; Alexander Hamilton relied on "The Federalist Papers" to do just that. But it surely is the first time that the tutorial originates with the taxpayers rather than the tax collectors.

President Bush's neglect of the tutorial function of the presidency helps explain his much-noted lack of eloquence. Mispronunciations and Texas speech patterns have nothing to do with Bush's failings in the realm of words. The president cannot speak to a deeper need unrecognized by his fellow Americans because the only need recognized by his political philosophy is self-interest narrowly understood. Fully cognizant of how ignoble his objectives would appear if stated in truthful terms, he therefore has little choice but to obfuscate, and obfuscation can never be transformed into eloquence. If the president's speeches so often fail to move, it is because he has not offered anything worth moving for; you simply do not rise to the heights of greatness by calling for the elimination of taxes on dividends. The wealthy he wishes to reward are too interested in lining their pockets to care whether angels, better or otherwise, are watching what they do.

This president's lack of responsibility is revealed not only by the policies he pursues, but by the way he pursues them. FDR was famous for soliciting conflicting opinions from those surrounding him so that he could choose from among them. It was not that he possessed the training in economics they lacked; on the contrary, they were the experts and he was the politician. But he did possess the wisdom that experts often lack. And he relied upon that wisdom for his famous flexibility; Roosevelt was quite capable of shifting his positions as new advice came in without ever paying a price at the polls.

Although Bush receives conflicting advice on foreign policy -- the disagreements between the departments of State and Defense in this administration are as public as any disagreements among FDR's advisors -- no such squabbles are permitted on domestic policy. By surrounding himself only with people who share the same point of view, Bush all but acknowledges that in this area he has no instincts -- and thus, no wisdom -- of his own to offer. If the country ever needed evidence that deep tax cuts are fiscally untenable, the unbending convictions offered to justify them are evidence enough. Economies are governed by real-world actions, not principles drawn from textbooks. Any administration that meets all criticism with citations from the latter and a blind eye toward the former lacks not only wisdom, but the intelligence needed to know where to find it.

The experience of Bush suggests that we need to be careful in selecting the virtues that make for great presidential leadership. Setting a course requires courage and determination, the virtues so admired by Kennedy, and Bush surely has the one and has shown the other. But ensuring that the course is a good one demands virtues of another sort. There is the virtue of discernment, the ability to weigh competing policies and select the ones that best correspond with America's values and long-term goals. There is the virtue of humility, manifested in a willingness to admit mistakes and redraw plans. And there is the virtue of confidence, the ability to treat those who disagree with you with respect.

Without those qualities, firmness becomes intransigence, initiative morphs into arrogance, and conviction is transformed into dogma. Bush's ability to stay on message, so vital to getting him where he is, is the major obstacle in his path of going any further. Should he persist in the methods of governance he has chosen -- and there is no reason to believe that he will not -- Millard Fillmore beckons, not Abraham Lincoln.

Shares