I observed brain surgery once. For several hours I stood behind two surgeons as they successfully removed a tumor from a woman's brain, then put her back together. It was fascinating to watch, and surprising how much the procedure resembled carpentry -- fine cabinetwork, but carpentry nonetheless. Recently I discovered something equally surprising: Managing national and international affairs as practiced at the chief executive level is a lot like carpentry, too -- but not fine cabinetwork.

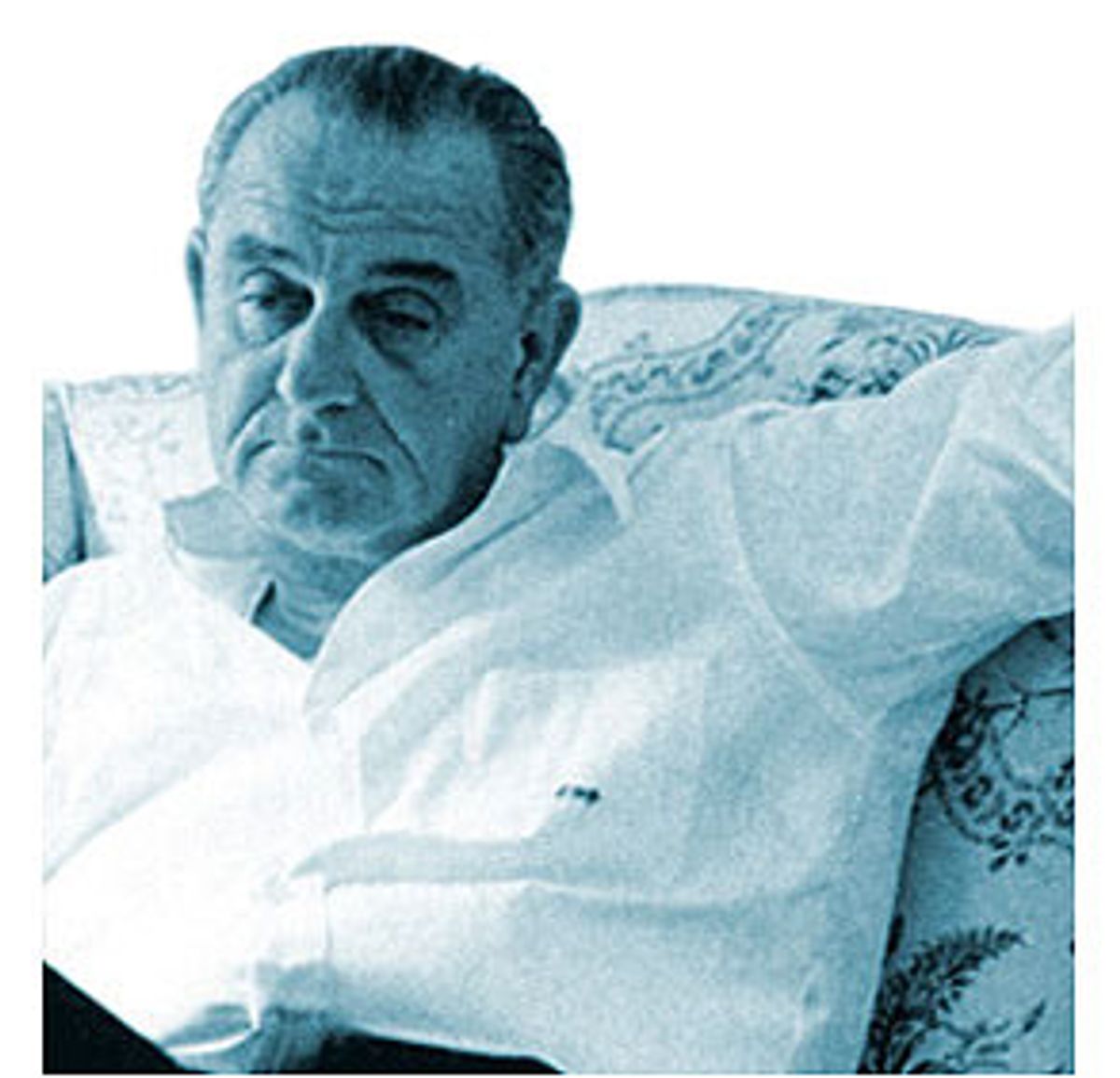

I've been reading and listening to Michael Beschloss' "Reaching for Glory: Lyndon Johnson's Secret White House Tapes, 1964-1965," the second volume in a trilogy, which also comes as a set of six CDs. (The first volume, "Taking Charge: The Johnson White House Tapes, 1963-1964," was published in 1997.) For anyone, but especially for those who lived through Johnson's presidency -- a time when the country was coming unglued domestically and what LBJ called "that bitch of a war" was exporting the American nightmare to Southeast Asia -- "Reaching for Glory" is not only compelling, it's an addictive lesson in how history is hammered together, often with little attention to craftsmanship. (The audio version is an essential complement to the print book; if you must choose one or the other, get the CDs.)

There are conversations between the president and J. Edgar Hoover, George Wallace, Robert McNamara, Robert Kennedy, Hubert Humphrey, Martin Luther King, Bill Moyers, McGeorge Bundy, Dean Rusk, John Connally, Gerald Ford, Dwight Eisenhower, Harry Truman and numerous other key figures from inside and outside the administration who governed the country during some of its most fractious, polarized years. All the wide brush strokes of U.S. history made from September 1964 through August 1965 are here -- the Johnson vs. Goldwater election ("We've got a bunch of goddamned thugs here taking us on"), Vietnam ("I don't think anything is going to be as bad as losing, and I don't see any way of winning"), civil rights ("If Alabama won't let a Nigra vote because of the poll tax and I can prove it, I'll go directly to the Supreme Court") -- but the undertones, the personal shadings as rendered in tangential conversations and Lady Bird Johnson's tape-recorded diary entries, which appear throughout the book, are often just as illuminating. (As Richard Reeves pointed out in a recent interview while discussing Pat Nixon's role: "What spouses do for you is tell you who you can trust.")

In the case of Lady Bird's diary, which she recorded virtually every day (it's convincingly read by Judith Ivey on the CDs), the first lady is the subtext that makes LBJ's hewing of the main plot points all the more intriguing -- or is he the subtext? For those more captivated by what happens on the periphery of history than the giant steps themselves, the side stories are the most revelatory: It's there where the players' personal constitutions appear in high relief, and as any novelist or screenwriter will tell you, the best tales are those where character drives plot. And it's in the president's personal discussions, with Lady Bird, his daughters and others, where you get the fullest sense of his nature. Emotional, almost fragile, LBJ was complicated and complex-ridden, a classic tortured soul wrapped in the armor of a charming and formidable operator.

The book begins with a prologue -- an eerie phone conversation between Jacqueline Kennedy and Johnson, which took place on the afternoon of Dec. 2, 1963, just 10 days after President Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas. As with all the conversations in "Reaching for Glory," LBJ was the only one who knew it was being recorded.

Jacqueline: Mr. President?

LBJ: I just wanted you to know you were loved and by so many and so much and ...

Jacqueline: Oh, Mr. President!

LBJ: ... I'm one of them.

Their chat continues in that vein, with Jackie referring to a supportive note LBJ had sent her the day before and a response she'd sent to the president through JFK's appointments secretary. Johnson tells Jackie to call him anytime, he flatters her, reassures her, they joke a little. It probably didn't last more than a couple of minutes, if that. The eeriness comes from hearing Jackie's voice -- a pain-filled baby-doll whisper from far out on the ragged edge of misery: raw, exhausted, on the verge; it's a Betty Boop-like caricature of a female voice.

LBJ: Listen, sweetie. Now, the first thing you've got to learn -- you've got some things to learn, and one of them is that you don't bother me. You give me strength.

Jacqueline: But I wasn't going to send you in one more letter. I was so scared you'd answer.

They talk a bit longer, then it ends:

Jacqueline: Thank you for calling me, Mr. President. Goodbye.

LBJ: Bye, sweetie. Do come by.

Jacqueline: [warmly:] I will.

Throughout their conversation, her inflection hauntingly resembles the kittenish tones of Marilyn Monroe singing "Happy Birthday" to JFK, while LBJ sounds like a comforting uncle, perhaps a little too willing to lay on the comfort. (In another phone call, five days later, he closes by saying, "Give Caroline and John-John a hug for me . . . Tell them I want to be their daddy!") The Dec 2. conversation, with its novelistic foreshadowing, is the perfect opening scene -- a beautiful widow at the threshold of collapse talking with the man about to preside over a country going out of its collective mind both at home and abroad, and, ultimately, his own physical, emotional and political ruin.

Jackie liked LBJ -- she was apparently the only Kennedy who did -- and years later would praise his "incredible warmth" and "generosity of spirit." These aspects of Johnson's personality, the tapes make clear, were authentic -- but they were lost on many at the time he was in office. Those who were opposed to what first Barry Goldwater, then millions of others, called "Johnson's War," had a hard time then (and still do) seeing what a multidimensional character LBJ was. Even those who supported him politically, like the Kennedys, derided him for his folksiness, his unrelenting Southernness, his lack of polish. But he was the canniest of politicians, an extremely bright man (perhaps not truly brilliant like Nixon or Clinton, but plenty sharp) and gifted with a powerhouse intuition. Too bad he didn't pay more attention to it: Beschloss contends that it was Kennedy holdovers such as McNamara, Bundy and Rusk who convinced LBJ that JFK was intent on escalating the war, and that if he didn't follow through, the dead president's ambitious brother, Robert, would brand Johnson as soft on Communism. It's a contention that the tapes seem to confirm.

In a Sept. 18, 1964, conversation with McNamara, Johnson's instincts are spot on as he listens, and continually expresses skepticism, while his secretary of defense tells him that two American destroyers may be under attack in the Gulf of Tonkin off North Vietnam. The month before, the Tonkin Gulf incident had occurred (on August 4), and as McNamara and LBJ talk about this new "attack," it becomes clear that the president already suspects that the August event was a false report (a suspicion that would later be confirmed). "Now, Bob," Johnson says, "I have found over the years that we see and we hear and we imagine a lot of things in the form of attacks and shots ... Take the best military man you have, though, and just tell him that I've been watching and listening to these stories for 30 years before the Armed Services Committee, and we are always sure we've been attacked. Then, in a day or two, we are not so damned sure. And then in a day or two more, we're sure it didn't happen at all!"

"Yeah, yeah," McNamara responds, then continues to make his case:

McNamara: We've got a number of messages here now and considerable evidence that, as I say, there was either an intentional attack or a substantial engagement. I differentiate one from the other.

LBJ: Well, what is a substantial engagement? Mean that we could have started it and they just responded?

McNamara: But they stayed there for an hour or so. The first --

LBJ: They would have been justified in staying, though, if we started shooting at them.

As you listen to the "Reaching for Glory" CDs, a portrait emerges of Johnson as a man of a thousand faces and dozens of personalities, all of them real. It wasn't that he was duplicitous, he was kaleidoscopic. With women he's overtly flirtatious, he charms, he playfully admonishes, he compliments their appearance (to Jackie: "Your picture was gorgeous. Now you had that chin up and that chest out and you looked so pretty ..."). With men he cajoles, bluntly questions, he's crude, sophisticated, overbearing, a dick-swinger of the first order. (His March 1, 1965, upbraiding of New York Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. rivals performances by Pavarotti and Robert Plant.) He's also a mass of insecurities; Nixon would beat him in the paranoia sweepstakes, but only by a nose. And when Lady Bird misses seeing him on television he becomes a petulant little boy:

LBJ: Didn't see the television tonight, did you?

Lady Bird: No, darling, I didn't ...

LBJ: [irritated:] Well I was on, you know, nationwide. The first nationwide television at nine-thirty Washington time ... Didn't you know about it?

Lady Bird: Yes, I knew about it, but I didn't know the timing on it, darling.

LBJ: Why in the hell don't you find out?

That exchange took place a month before the 1964 election. Just a week later his problems became considerably more severe than whether the first lady caught him on TV. Walter Jenkins, special assistant to the president and a longtime Johnson friend, was arrested for performing oral sex on another man in the restroom of the Washington, D.C., YMCA. LBJ's personal attorney, Abe Fortas, called to give Johnson the news. After Fortas begins the conversation by going on vaguely, circuitously and at considerable length without ever managing to convey to the president exactly what he's talking about, he asks Johnson, "Have I gotten this across at all to you?"

LBJ: No.

Fortas: Well, is it all right to talk on this phone?

LBJ: Yes, I think so.

Fortas then proceeds to awkwardly meander around the subject for another long paragraph before LBJ responds: "I can't hear you. Talk a little louder!" The president finally gets the idea and twice says, "I just can't believe this." He's sure that Goldwater's behind it, that it's a setup, but Jenkins has confessed and he leaves the administration.

It was a sad episode, and it's a minor footnote at this point, but if any good came out of it it's the current entertainment value of the Halloween 1964 conversation between Johnson and J.Edgar Hoover. After the Jenkins calamity, LBJ calls Hoover to see if FBI investigations have turned up any other homosexuals in the Johnson administration. Hoover says the agency's investigating one Navy man in the Defense Dept. "In the course of the conversation," Beschloss writes in a short preamble, "despite longtime rumors that he is himself involved with his housemate, Deputy FBI Director Clyde Tolson, Hoover lectures on how to spot a secret homosexual."

LBJ: They raised the question of the way he combed his hair and the way he did something else, but they had no act of his ...

Hoover: It's just ... that his mannerisms ... were suspicious.

LBJ: Yeah, he worked for me for four or five years, but he wasn't even suspicious to me. I guess you are going to have to teach me something about this stuff. ... I swear I can't recognize them. I don't know anything about them.

Hoover: It's a thing that you just can't tell sometimes. Just like in the case of the poor fellow Jenkins ... There are some people who walk kind of funny. That you might think a little bit off or maybe queer.

You have to wonder if the president was just messing with the humorless Hoover or if he was actually as unworldly as he implies. (It's vaguely reminiscent of his exchange with Charles De Gaulle. On a presidential visit to France, so the story goes, De Gaulle met LBJ at the airport and in the motorcade on the way into Paris asked him haughtily, "So, Mr. President, what can we teach you?" To which the sly good ol' boy and commander in chief replied, "Why, just every little thing.")

But the light moments in "Reaching for Glory" are few. Overall it resembles one of those docudramas in which you know what the dreary dénouement is and you simply have to watch (or listen) as the players career toward it. It's like viewing slow-motion film of a train wreck -- though we won't see the full force of the collision until the third installment of Beschloss' trilogy, which will cover Johnson's final years in office.

As for Beschloss himself, he's accomplished a terrific job of historical scholarship while being the perfect host -- he gives enough context for each conversation to enable readers and listeners to keep their bearings, then he steps out of the way and lets the dialogue carry the scenes. The exchanges are by turns astonishing, confusing, clunky and contentious. They're rarely elegant and they're fraught with the varying agendas of the characters, some of whom are high-minded and with the country's best interests at heart and others who, well, you've got to wonder. What's abundantly clear is that running the USA is tough, exhausting, nearly impossible work that lacks both the precision and success rate of brain surgery.

This story has been corrected.

Shares